Even as a child, Dong Zhaoxia worked well with children. She was patient and nurturing, a born teacher. It surprised no one that she majored in education at university. Instead, the surprise came shortly after graduation when she left her job in a primary school to become a kindergarten teacher.

Although the children were only a slightly younger, their educational requirements were entirely different, a situation for which Dong was woefully unprepared. Gazing into the expectant faces of her two-dozen pupils, she was all but overwhelmed.

In fact, many educators in rural China have stories similar to Dong’s: with little or no training in pre-school education they switched from teaching primary or middle school to teaching kindergarten. This trend coincided with the rapid proliferation of kindergartens, a result of the State Council’s Three-year Action Plan for Preschool Education. Enrolment rates rose quickly, but there were far too few formally trained kindergarten teachers to answer the increased demand. According to a survey of over a thousand full-time rural kindergarten teachers, nearly half lacked training in pre-school education.

Creating a Curriculum

Dong struggled to develop a curriculum appropriate for her students. Those she’d relied on when teaching primary school were unsuitable for preschoolers. She studied any available resources and searched online for additional information. Then one day she received a preschool activity book from Thousand Trees. It was filled with age-appropriate stories, activities and songs. There were also extensive notes and instructions on how to engage the pupils, as well as references to short videos that demonstrated teaching methodologies. Dong was thrilled to have such a useful educational tool and quickly became more confident in her teaching. It was the children, however, who benefited most.

Telling Stories

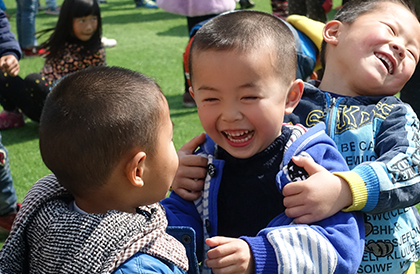

“When I first started teaching here, the children were so shy they barely spoke, no matter how much I encouraged them,” Dong recalls. “But everything started to change when I began reading stories from the Thousand Trees book. They’re colorful and well written, maybe even a little challenging, but the children were captivated.” Within two months of receiving the book, her class had undergone a dramatic change. “I read a story and asked for a volunteer to retell it, and at least half the children put up their hands. That’s what it’s like now,” she says, smiling. “The children want to express themselves.”

In creating materials for kindergarten teachers, Thousand Trees looked to the educational theories of Lev Vygotsky, who originated the Zone of Proximal Development (ZVD). Vygotsky believed that a child’s learning potential is determined by two variables: 1) what a child can learn independently; and 2) what a child can learn under guidance from a teacher, which indicates the ZVD. By taking into account the ZVD of children raised in rural China—based on environment and upbringing—Thousand Trees was able to develop materials that were best suited to them.

The Virtuous Circle

Providing rural kindergarten teachers with efficient educational tools will, Thousand Trees believes, create a virtuous circle: “The materials we supply help teachers engage their students by organizing interesting learning activities. Then the teachers perform better and become more confident. Children enjoy the activities, have positive interactions with their teachers and learn more. Positive feedback makes teachers even more motivated. Children become increasingly comfortable with their teachers, which further improves classroom interaction. This is the virtuous circle we want to create.”

Having experienced the virtuous circle, Dong Zhaoxia is now truly at home in her position as a kindergarten teacher. As she stands before her class, the expectant faces of her students now excite and motivate her, for this is where their future begins.

The little girl in the blue dress reads aloud from a storybook, the younger children crowding around her. She is perhaps eight years old, and her short braids bob playfully as she reads with such intensity that her audience is left spellbound. The little girl’s name is Tiantian. She is the youngest volunteer at the Thousand Trees Children’s Home.

Born in Northeast China, Tiantian and her mother migrated to Beijing when she was three years old. There, they reunited with her father who had found work as a carpenter in the Tongzhou District.

Little Tiantian was an emotional child, both quiet and temperamental. Concerned about her daughter’s development, Tiantian’s mother sent her to Thousand Trees, a kindergarten known for its unique approach to teaching.

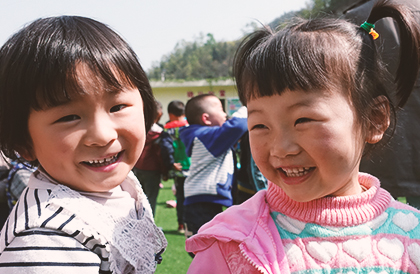

Almost immediately, her mother noticed a change. Tiantian became enthusiastic about school and looked forward to going each day. Before long, there were signs that she had matured socially: Tiantian was now able to empathize with other children, rather than see them as adversaries. Most surprising was that this once quiet child now came home from school eager to perform songs and tell stories.

One day, Tiantian’s mother came to pick her up from school, and the teachers invited her to stay and participate in the Learning Community. An initiative that aims to form an educational alliance among teachers, parents and children, the Learning Community focuses on the development of social skills and problem-solving abilities.

In the activities held by they Learning Community, teachers and parents shared many education concepts and techniques, and Tiantian’s mother quickly became an active member. “In the past, I didn’t know what to do with her,” Tiantian’s mother admits. “Sometimes I’d just put on cartoons for her to watch. Now I have a much better sense of how to engage my daughter and how to guide her development. I also understand her better, which makes me to appreciate her efforts even more.” With that she showed us Tiantian’s “works” from 3 to 8 years old. “I’ve stored all her paintings on my phone.”

The Storytelling Club help kids to form a habit of reading and enhance parenthood. Tiantian and her mother are both fervent supporters of it. Tiantian’s mother has made it a habit to read to Tiantian, and she is a frequent visitor in the Children’s Home library. When Tiantian was in pre-k class, she could read picture books aloud for half an hour all by herself.

Currently a second grader in primary school, Tiantian still returns to the Thousand Trees Children’s Home to participate in storytelling, arrange books and read to the children. When asked why she volunteers, she explains, “I really liked it here. I liked the storybooks and my teachers. They read to us, played games with us, and let us choose the activities we liked best.”

In a moment of shyness, she hides her face behind a book, leaving only her eyes visible. “Now I can read books to my younger brothers and sisters here,” she says softly. Her eyes brighten, and even though the book covers her face, it cann

When I was a child, my family ate fish from the nearby Yangtze River. Very often, I would end up with a fishbone lodged in my throat. No one else seemed to have this problem, and it made me wonder what I was doing wrong. My mother called me her little glutton, and said it was because I was too impatient and clumsy—that I needed to slow down and proceed thoughtfully. It would be many years before I fully embraced the wisdom of my mother’s words.

I joined Thousand Trees two years ago, and I was nothing if not passionate. But I was also blindly self-assured and assumed that because I was doing something for the common good, I could solve everything. Several times, I visited each of the 71 rural kindergartens under my charge in Hubei Province. My thinking was simple: if I keep a close eye on these schools, they’ll get better. During each visit, I would speak about activity design and field theory. I would go on and on about teacher responsibility and life missions. In hindsight, the teachers were probably thinking to themselves, “Talk is cheap.” For it’s one thing to spout theory, and another thing entirely to face the practical realities of teaching kindergarten in rural China.

During a school visit in the spring of 2015, a teacher politely told me, “It would be better if you didn’t come here. We’re under extra pressure to prepare for the demonstration course. You can inform the Education Bureau that we want out of the program.” I was dumbfounded. Why would the school reject such a good thing? The local Education Bureau told me they would “learn more about the situation,” but they never got back to me.

Once again, a fishbone had become lodged in my throat.

After returning to Beijing, I was in low spirits, but I did not want to give up. Instead, I applied for a short-term position at Thousand Trees Children’s Home in the Tongzhou District. It was here that I learned just how impractical my approach had been. For instance, I had instructed teachers to be mindful of their intonation when reading a story, to use the appropriate facial expressions and body language. But when it was my turn to read, my face and body remained frozen. I had also insisted that teachers to ask open-ended questions in order to facilitate discussion, but when I tried it, the students were unresponsive. Slowly, I began to see things from the teachers’ point of view, and this newfound empathy had a dramatic impact on my approach to work. I began to listen more carefully. I became more patient. And my reviews were more positive, for I better understood the many challenges faced by teachers.

In the latter half of 2015, I was assigned to Gansu Province. Thousand Trees had recently begun promoting its projects on a much larger scale, and the kindergartens under my charge increased from fewer than 100 to over 1,000. The project was launched simultaneously in eight counties, but within a few months there were serious issues. Some counties had no secondary training, researchers and trainers weren’t visiting schools, and some schools were ignoring the curriculum. Faced with these problems, I slipped back into my old habit of impatience. This time it was directed at the local Education Bureau, who appreciated it no more than the teachers had.

Yet another fishbone was choking me.

Some time later, I found myself strolling around a small playground with the Chief Scientist of Thousand Trees, Professor Zhang. It was night and the temperature had fallen well below zero, but the cold was far less daunting than the problems I faced. “What should I do?” I finally asked him. Smiling patiently, Professor Zhang said, “It’s not as easy as you thought to supervise projects. Nothing happens overnight. It would be a great achievement if all the teachers could read the stories properly by the end of the first semester. Perhaps you should speak to the local Education Board about making reading a priority and focus on this one thing.” This answer surprised me. “Focus only on one thing?” Professor Zhang nodded, “Doing one thing well is a great achievement.”

I gained additional insight from Zhao Hongzhi, who had supervised a renowned project called Western Sunshine. “Before I was in charge of the project, I’d been a volunteer teacher in Gansu Province for three years,” he explained. “It’s very important that you listen to the Education Bureau, the principles of rural kindergartens and the teachers themselves.” I took these words to heart, and when I returned to work, I spent more time observing the teachers and listening to the principles as they articulated their needs. I had fruitful discussions with officials of the Education Bureau.

Once again, I heeded my mother’s advice to slow down and proceed thoughtfully. In doing so, I was able to see so much further and learn so much more.

It’s been three years since I began working in the non-profit sector, and although I’ve made progress, I still have a lot to learn. Ironically, I’m now the one telling others to slow down, to be patient, to take things a step at a time. My experience has taught me that pre-school education in rural areas faces a unique set of complex problems, factors such as the educational background, salary, assessment, and motivation of a teacher should be taken into consideration in order to come up with any solution. It’s never been a question of who’s to blame. It’s a matter of identifying the underlying causes and addressing them. This requires commitment, empathy and above all, patience.

How do we make pre-school education in rural China better? There is no panacea for such a complex situation. There is, however, a logical path to improvement. On this path, we strive to understand the real problems faced by teachers and administrators. We address these problems thoughtfully, understanding that results take time. Finally, we take advantage of the incredible innovations the digital age as provided, innovations that have already been so helpful in solving social problems around the world.

This is how we avoid the fishbone.